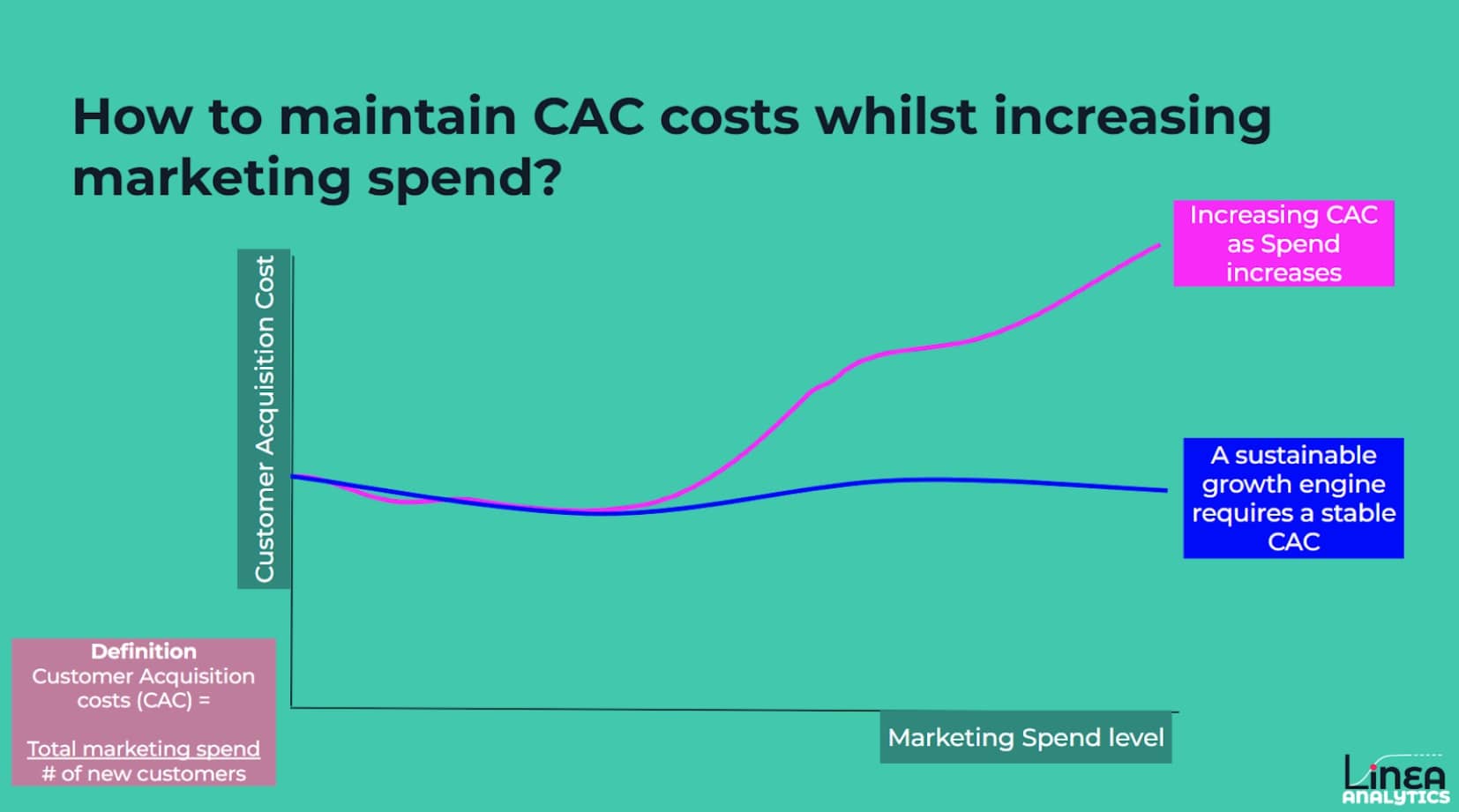

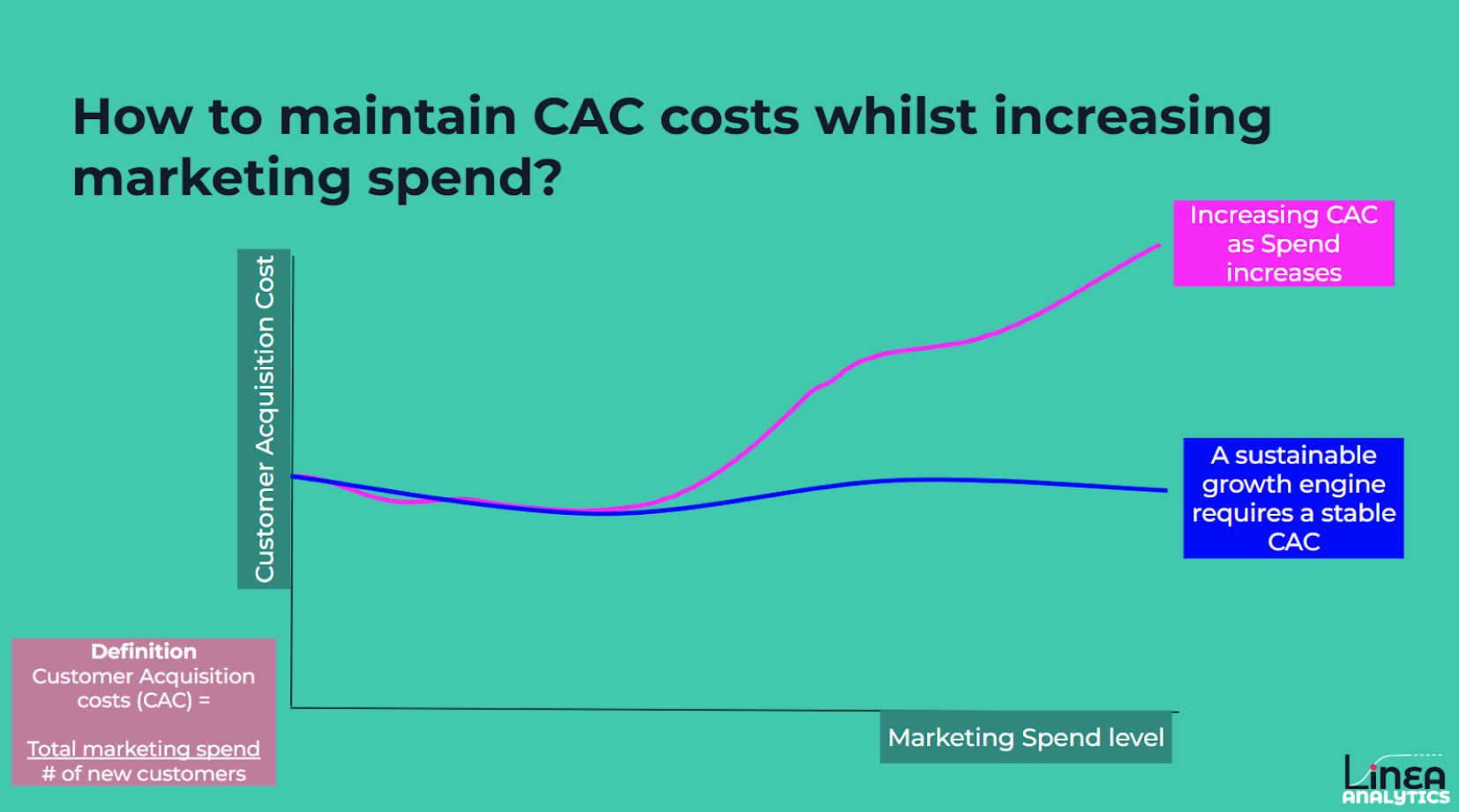

If we keep scaling media spend, will my CAC always increase?

It’s the classic question Harry Stebbings asks founders on the 20VC podcast, and it gets right to the heart of an age-old principle: diminishing returns.

Let's briefly start with a definition. It is defined as the:

$ \text{CAC (Customer acquisition cost)} = \frac{\text{Total Marketing Spend}}{\text{Total New Customers}} $

CAC is different to CPA (cost per acquisition). Whereas CAC focuses on the total marketing spend. CPA focuses on the spend of an individual channel/ campaign/ creative.

$ \text{CPA (Cost per acquisition)} = \frac{\text{Amount Spent on a Marketing Campaign or Channel}}{\text{New Customers from Marketing Activity}} $

As you spend more on the same marketing channels, the efficiency of your spend drops.

Why does that occur?

🎯 Frequency: Your ads are hitting the same people again and again

📉

Reach: There's a finite audience within any given channel

Many brands see CAC increasing as spend levels increase

So how do you prevent CAC from spiralling upwards as you scale?

🔍 Double down on what’s working

Not all ad spend is effective. There’s always some

waste. Rigorous measurement is essential to identify what’s actually driving acquisition and trim the rest -

this is the easy step 1.

📊 New channels = new audiences

Once you saturate your early channels, you need to expand

reach.

Monzo is a great example. In 2019, they jumped from acquiring 150k customers per week to 250k — not

by spending more in the same places, but by moving beyond digital and into TV.

📢 Brand to drive future demand

Performance marketing captures demand. Brand marketing

creates it. Investing in brand marketing builds awareness and expands the pool of future customers.

Which, over time, supports more efficient acquisition.

And if CAC still rises?

Then it’s time to focus on the other side of the equation:

💡 Hold CAC steady and grow LTV.

Greater retention, higher basket sizes, and upsells all drive better unit economics even if CAC stays flat or increases slightly.